The effects of climate change are an additional burden African economies are currently having to navigate in a global environment defined by multiple crisis ranging from the lingering effects of the outbreak of COVID-19, acute debt distress, the effects of the Russia-Ukraine crisis and new highs in the cost of foreign capital.

The effects of climate change that have more direct economic impacts include:

- Hotter temperaturesthat increase heat-related illnesses and cause other effects listed below.

- More severe stormscausing more flooding and landslides, and destruction of property and communities.

- Increased droughtdue to water scarcity, desert expansion, and reduction of land available for food production.

- Rise in hungerdue to increases in extreme weather events and heat stress that destroy crops, fisheries, and livestock or make them less productive.

- Poverty and displacementdue to extreme weather events that destroy homes and livelihoods. Weather-related disasters displace 23 million people a year, leaving many more vulnerable to poverty.

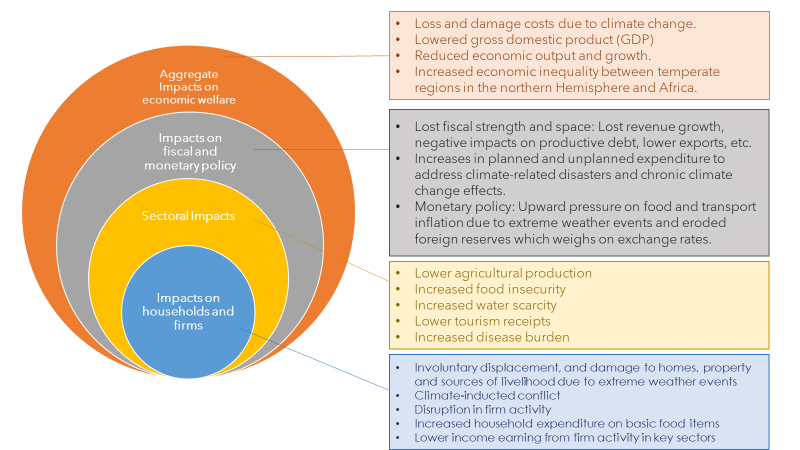

Climate change has layered impacts on Africa from macroeconomic effects, to targeted sectoral effects and microeconomic impacts on firms and households.

Macroeconomic effects

There are three main macroeconomic effects being borne by African governments:

- Lost and lowered economic growth and activity;

- Fiscal policy: Lower revenue, higher expenditure and compromised debt sustainability;

- Monetary policy: Upward pressure on food and transport inflation due to extreme weather events, and eroded foreign reserves which weigh on exchange rates.

Rising temperatures and changes in rainfall are affecting economic activity more in sub-Saharan Africa than elsewhere. The African Development Bank estimates that loss and damage costs due to climate change in Africa is between $289.2 billion to $440.5 billion. The combined macroeconomic effects of climate change could lower the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP) by up to 3 per cent by 2050. Further, climate change has reduced economic output and growth in Africa more than other regions in the world. Indeed, global warming has increased economic inequality between temperate regions in the northern Hemisphere and Africa.

In terms of fiscal policy, revenue is being hit as climate change is changing rainfall patterns leading to prolonged periods of both drought and flooding depending on the region. This interferes with agricultural production where agriculture constitutes almost a quarter of the continent’s GDP and yet is almost entirely rain-fed. Lower agricultural productivity translates to lower revenue generation potential from a crucial and large sector and interference with export receipts and forex earnings.

It is estimated that African countries are already spending between 2 and 9 per cent of their budgets in unplanned allocations to respond to extreme weather events. Between 2005-2020 flood-induced damage in Africa was estimated at over USD 4.4 billion, and 8 of the 20 countries with the highest expected annual damages to road and rail assets, relative to the country’s GDP due to climate change, are in Africa. Climate-related damage to infrastructure is not only interfering with the multiplier effects of infrastructure investment, it compromises the productive potential of debt, putting millions of dollars at risk for which African governments are still liable. The impact of weather on transport infrastructure also has the monetary policy effects of raising the cost of transportation as infrastructure is damaged or made impassable – these costs are passed on to consumers, placing upward pressure on inflation.

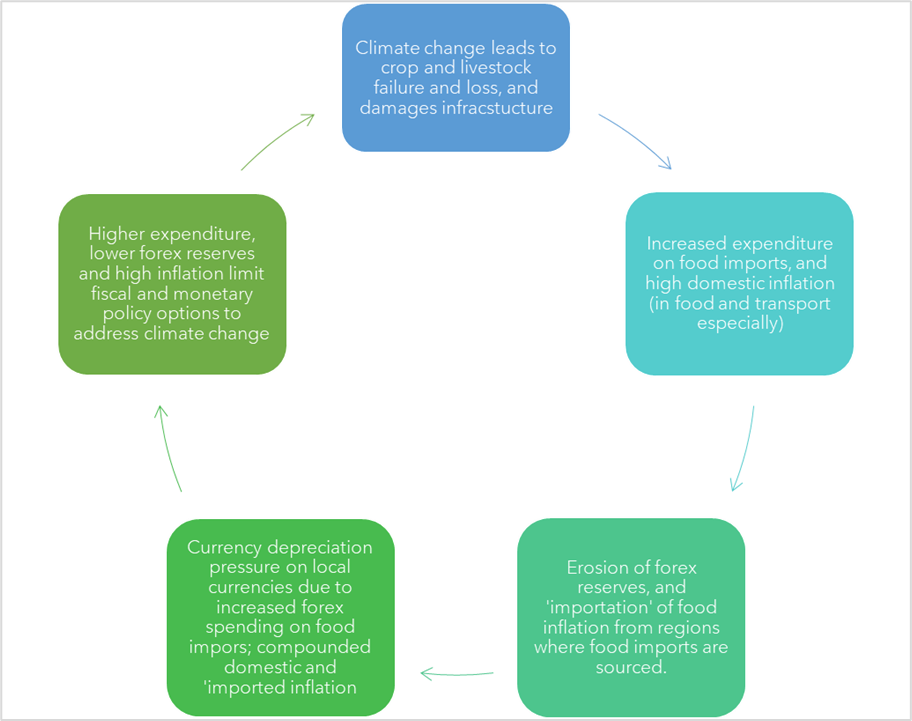

Consequently, climate change has negative impacts on debt sustainability as it interferes with revenue generation and thus repayment capabilities in both local currency and USD. In addition, increased climate-induced expenditure haemorrhages money to meeting those costs. The combined effects of climate change on fiscal and monetary policy creates vicious cycle as below:

Source: Were, A., The impacts of climate change on fiscal and monetary policy in Africa, illuminem, 2023

Sectoral effects

Climate change disproportionately affects key sectors— agriculture is of particular concern not only because it constitutes almost a quarter of the continent’s GDP but because most Africans rely on the sector as a key source of livelihood. The negative impacts on this sector increases food insecurity and under current climate projections, Africa will lose up to 16 per cent of GDP as a result of malnutrition alone by 2050. Given more erratic rainfall, the water sector is of concern given one in three Africans face water insecurity and approximately 400 million Africans lack access to clean drinking water. Tourism in Africa is particularly natural-asset dependent; rainfall variability, extreme heat and drought lower animal mobility and alter wildlife migrations, affect tourist visits. Yet the sector accounts for about 8.5 per cent of Africa’s GDP, of which wildlife tourism contributed a third of tourism revenue, supporting 8.8 million jobs in 2018.

An often-over-looked sector is health where climate change is already negatively impacting certain health outcomes. Increasing global warming is expected to increase Africa’s disease burden due to the expansion of malaria-prone areas; increases in diarrhoeal diseases due to extreme rainfall increasing, cardio-respiratory issues (due to dust storms and wildfires), and the severe mental health effects in individuals impacted by extreme weather events.

Microeconomic effects

Households are directly impacted by extreme weather events which lead to involuntary displacement, and damage to homes, property and sources of livelihood. Indeed, in 2020, 1.2 million Africans were displaced by floods and tropical storms; and business disruptions from climate impacts have implications for deepening poverty. Further, climate change increases the likelihood of conflict; a 1°C higher temperature is associated with a greater risk of conflict in Africa of about 11 per cent, increasing household and community displacement, relocation and insecurity.

Layered economic effects of climate change on Africa

It is grim and unfair to expect Africans to continue to shoulder the effects of a crisis they did little to create. And it is unseemly that African governments are not losing only current and future economic, fiscal and monetary policy space to climate change, but that this comes at a time when these fiscal and monetary policy options are needed.

How climate finance can help

- Prioritise investment into climate-smart and resilient infrastructure: Climate change is not only interfering with the multiplier effects of infrastructure investment, but also compromising the productive potential of debt linked to these investments. This can be addressed by infrastructure financiers adopting a default climate lens, in all infrastructure-related investments in Africa going forward. This investment will meet Africa’s $100 billion per year infrastructure finance gap, and can consist of new climate-smart infrastructure to mitigate the impacts of extreme weather events; as well as climate-proofing existing infrastructure.

- Green Recovery Bonds: Given the debt crisis that many African countries are facing and the impact climate change is having on debt sustainability, Green Recovery Bonds can be leveraged where creditors swap old debt for sustainability-linked bonds that are enhanced by a guarantee facility. The bonds would be sustainability-linked with key performance indicators rooted in African government green and climate plans.

Source: Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery, 2023

The Debt Relief for Green Recovery (DRGR) Project proposes a ten-year maturity for the new bonds and a Secured Overnight Financing Rate +3.5 percent cost with a partial guarantee of the principal (80 percent portion) plus 18 months of interest payments fully guaranteed. The guarantee facility could be financed through unused SDRs or through the multilateral and regional MDBs existing balance sheet. Read this Financial Times article for more detail on the DRGR proposal.

Build green project pipelines to secure sector resilience and performance: Last year, I wrote an article here on how to develop a green project pipeline in Africa. In it, I proposed a shift in mindset from financing individuals deals to financing the financial architecture that supports the aggregation of deal flow:

Source: Were, A., How to develop a green project pipeline in Africa, BII, 2022

Given African economic growth will outpace global growth in 2023 and 2024, key sectors and value chains offer opportunities for climate and green investors to tap into Africa’s growing economies and markets. Collaboration between climate financiers, MDBs, DFIs and climate investors will enable finance to activate opportunities more effectively in Africa and build green project pipelines in energy and transport infrastructure, green buildings and housing, health, agriculture, water, and eco-tourism. Sustainable mining is a particularly promising opportunity given that the low-carbon energy transition is increasing demand for resources found in Africa such as lithium, cobalt, vanadium, copper, and selenium – and resource abundance in Africa is increasing, not declining.

Anzetse Were is a development economist and currently Senior Economist at FSD Kenya.

The views expressed in this article are the contributor’s own and do not necessarily reflect BII’s investment policy or the policy of the UK government.