What did we learn during our approach to the Ebola crisis?

View this article as a pdf document

In 2014-16, Sierra Leone suffered from an Ebola outbreak that tragically killed nearly 4,000 people. At the same time, the crisis put the brakes on the economic progress made by the country over the previous decade, with the annual growth rate of GDP falling from almost 9 per cent to minus 2 per cent.

The World Bank estimates that the economic impact from lost growth and investment was nearly $2 billion, more than half the country’s total gross domestic product, and the outbreak left 9,000 waged workers and 170,000 self-employed workers unemployed.

For many companies, in a country that was already difficult to do business in due to poor infrastructure and a lack of access to capital, the situation was made worse. There were shortages in the supply of basic commodities and disruptions to supply chains, as well as reduced production from the mining sector, which the country had previously relied upon to bring in foreign exchange. As a result, many businesses were left with acute shortages in accessing capital, with serious implications for jobs. During that crisis, as is the case during the current Covid-19 pandemic, CDC’s focus was to find a way to channel much-needed liquidity to local businesses.

Are there parallels in the situation Sierra Leonean businesses faced during that epidemic and the situation many businesses face as a result of Covid-19? What approach did we take six years ago and why? And how is it informing our current approach as we work to strengthen the impact we have can have in Africa and South Asia?

Huge disruptions to normal business activity

For both businesses in Sierra Leone affected by the Ebola crisis, and businesses during the current Covid-19 pandemic, there are similarities. The dynamics of an epidemic or pandemic affect the ability of businesses to operate normally, which creates enormous financial strain.

Firstly, there is the impact of stringent lockdowns and social distancing, as well as a broader economic downturn brought on by the crisis – for example businesses can’t sell to consumers, and they can be affected by disrupted supply chains. And secondly, there is an indirect effect – because of the crisis, capital providers such as banks and investors get nervous, and this affects businesses’ ability to raise the capital that they so desperately need. All this means there’s a dual impact – businesses are unable to bring in revenue, while at the same time they can’t access credit either.

Back in February 2015, our approach was to partner with Standard Chartered Bank, to approve a ‘risk participation facility’ that would increase lending to their business customers in Sierra Leone to help them keep going through the crisis. Due to the constraints of ‘risk limits’, the bank was not able to provide as much working capital as it would like to these businesses. By sharing the default risk 50/50 between CDC and Standard Chartered, the facility allowed the bank to go beyond these constraints and to support new working capital lending of up to $50million.

The facility was designed to support borrowers in a variety of sectors, particularly those that had been negatively affected by the challenges to importing brought on by the crisis, including manufacturing, trading, and logistics. Originally designed to last for two years, it was rolled over twice, in 2016 and 2018, with the later facilities supporting businesses in Sierra Leone more generally, rather than specifically related to Ebola.

$50m

Our facility with Standard Chartered allowed the bank to support new working capital lending of up to $50 million.

Delivering rapid solutions to companies in need

The first lesson we learnt at the time was that speed was critical, and we needed an approach that was going to help us act as quickly as possible. Our regular due diligence processes – incredibly important to ensure that our capital goes to the right places – are more difficult to carry out in the same way during emergency situations. By partnering with a commercial bank like Standard Chartered Bank, we were able to deliver solutions to companies that needed a fast response. At a time when it was difficult to carry out on-the-ground due diligence, working with a trusted partner like Standard Chartered, whose customers were already well-known to the bank, had an advantage.

Geoff Manley, CDC’s lead on the investment with Standard Chartered Bank back in 2015, says: “It was definitely a situation that required adjusting of some of the usual rules to be responsive to the crisis. In responding to the Ebola crisis, the timeline from start to finish was around two months. Being able to adapt your processes to achieve the speed required by a crisis situation is important.”

Speed has also been a critical factor during the Covid-19 crisis. For example, we have instituted new processes – such as fast-track investment committees – to ensure we can respond quickly to urgent needs.

Partnering to maximise our impact

Secondly, by splitting the risk with another partner, and taking advantage of that partner’s local knowledge and networks, the approach allowed us to both bring in more capital to the country and reach more companies than we could do otherwise. Geoff says: “We decided to go down a partnership route, because we wanted to get a multiplier effect on the capital we were deploying. We thought that by pooling capital, we could collectively bring more to the problem, and achieve more than we would on our own.”

It’s also important to choose a partner that brings different, and complementary, strengths to our own. We know that others can bring capacities and expertise to the table that we might not have.

Dania Siddiqui, Investment Manager at CDC, says: “A commercial bank, like Standard Chartered, has the deep relationships with existing local business customers that we may not necessarily have. Whilst, as a development finance institution, we have the risk appetite that commercial banks may not.” As a long-term investor, we’re able to invest in countries and sectors at times when it is challenging for mainstream investors to commit.

Dania also points out that we can play a role in encouraging banks to do more, for example encouraging them to provide the facility in the first place, ensuring banks take on at least an equal level of risk to us and that only new loans, rather than existing loans, are part of the facility: “This increases the availability of capital for the market”, she says.

Providing the right support to companies critical to the recovery

“In crisis situations”, says Geoff, “getting working capital to those businesses who can both support employment as well as import and distribute critical good and services, is vital.” In the case of the Sierra Leone facility, the partnership with Standard Chartered enabled us to invest in an area of the market that was critical to the recovery.

The businesses supported by the facility were small and medium-sized – which can suffer and be put under pressure during a crisis. We know that our most effective way of getting capital to this size of business is through partners such as investments funds and banks, rather than investing directly. The partnership meant we could get working capital to businesses in need.

It not only allowed us to provide investment to the right part of the private sector, but also in the way that they most needed support. Dania explains: “Working capital is what businesses suffering both during Ebola and now during Covid-19 most need to continue operations. At the same time, working capital facilities require the kind of monitoring which, as a development finance institution, we’re not set up to do internally. But for commercial banks, this is a core focus. That means that by partnering with these banks, we’re able to provide this kind of support much more easily.”

Strengthening environmental, social and governance practices

An important part of our involvement in a facility like this is to ensure that the finance provided meets appropriate environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards.

Firstly, we can strengthen our commercial partners’ own ESG policies; in the case of the Standard Chartered facility, we provided training for the credit officers at the bank’s head office in Freetown, which was over and above the support that its London-based ESG team could provide. Secondly, we also want to ensure that these practices then reach a wide range of companies – all those benefitting from the facility, and in some cases the bank’s wider portfolio of customers. We were hands-on in approving the companies borrowing from the Sierra Leone facility, putting in place accelerated ESG and business integrity checks, and retaining the ability to veto companies that didn’t meet these standards.

Guy Alexander, ESG Manager at CDC, who was involved in providing assistance on ESG matters to the Standard Chartered facility, says: “The setup of the facility was able to proceed at pace as there was a rapid exchange of portfolio information. That meant we could appraise potential customers and develop an efficient and effective approach with our counterparts at the bank. The training that followed was built upon trust and a sound understanding of each other’s processes, which was important given the situation in which the facility was developed”.

What was the impact?

Since 2014, a total of $60.5 million has been disbursed to companies from the original facility and its follow-on facilities. This includes companies like Benco Trading, an importer and distributor of construction materials and foods. As many ships were unable to dock in Freetown during the crisis, Benco was unable to bring in cement from Senegal. Benco borrowed $3 million, which enabled it to reorient its business to supply goods and services needed by the country as it recovered. The investment helped it to retain staff, and even enabled some workforce expansion.

It also includes Shankerdas & Sons, one of Sierra Leone’s oldest businesses, which also borrowed from the facility so that it could continue to operate during the crisis. Shankerdas manufactures a variety of goods, including drinks, water containers and candles, and employs around 1,000 people. The company also took at a second loan with Standard Chartered after the end of the outbreak, to allow it to build a new factory in Freetown.

Ensuring our money is additional, in other words that our investment wouldn’t have happened otherwise, for example through foreign or local banks, is important for a facility like this. We’re confident that our investment in Sierra Leone was one that wouldn’t have happened without the risk appetite of a DFI. No other investors were providing US dollars into Sierra Leone at the time, which were clearly needed by businesses, and the investment has been a major source of foreign direct investment into the country.

$60.5m

Since 2014, $60.5 million has been disbursed to companies from the original facility and its follow-on facilities.

A blueprint for future investment

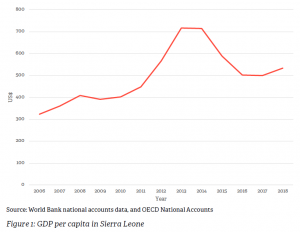

Whilst Ebola passed, Sierra Leone continued to suffer economically for several years following the outbreak from a lack of US dollars and from the fact that, as a small country, it imported a lot of materials and food. Even by 2018, GDP per capita was still far below its pre-crisis level (see Figure 1 below). As a result, the original two-year facility has been rolled over twice, in 2016 and 2018, to include some previous and some new borrowers.

The facility has not only informed our current approach to the Covid-19 pandemic – where we are exploring how we can support businesses who need urgent working capital to survive the period, by partnering with financial intermediaries such as local banks. It’s also influenced our approach to getting capital to Africa and South Asia through partnerships and intermediaries more generally. For example, it helped us to build on the trade finance programme we launched in 2013 – the difficulty of accessing trade finance is one of the key constraints facing local exporters and importers and limiting their growth. Through the programme, we’ve formed partnerships with regional and international banks across Africa and South Asia to guarantee $3.3 billion, resulting in $12.5 billion of trade across the two regions.

As we look to the immediate future, companies that are otherwise healthy will need urgent working capital to survive this period. Local banks will be crucial in providing funding to those companies buy will only be able to do that if organisations like CDC step forward. We’ll be working with financial intermediaries to help provide this liquidity, as we support businesses and economies through the recovery and beyond.

Find out more about our response to Covid-19 at cdcgroup.com/covid-19

$3.3b

Through our trade finance programme we’ve formed partnerships across Africa and South Asia to guarantee $3.3 billion.