This is the second of a two-part blog about what high interest rates mean for climate finance – the first part looked at subsidies for green investments when the cost of capital is rising.

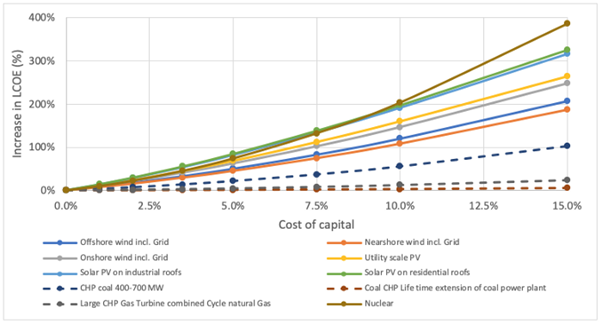

Interest rates are rising, which means if you want to borrow a lot of money to build a big infrastructure project, that’s getting more expensive. Renewable energy generation is capital intensive with low running costs; fossil generation is cheaper to build but has high running costs (fuel). The cost of capital can be responsible for more than half of the price of renewable electricity in developing countries. Jacob Kincer and Todd Moss have warned that rising interest rates are especially bad for clean energy in Africa, but more expensive finance may also affect the pace at which large carbon intensive middle income countries, such as India, replace coal.

One argument is that higher fuel prices are offsetting this problem, leaving renewables still looking comparatively good. This blog is about another argument: the difference between real and nominal interest rates. Anyone making the argument that higher interest rates will reduce investment in renewables is liable to have an economist jump out from behind a bush to inform them that actually investors care about real interest rates, not nominal.

To understand that you need to understand that economists think of inflation as the price level rising across an economy, so everyone’s ability to pay higher prices increases at the same rate as prices are increasing. Of course, economists understand that in reality different people’s nominal incomes change at different rates, and the present situation is so painful because prices are rising faster than most people’s nominal incomes are, so people are getting poorer in real terms. But the general idea is correct – inflation makes higher nominal interest rates more affordable. In an inflationary environment, that £100,000 mortgage you took out when it was five times your salary becomes less of a problem if your salary inflates. Loan contracts are nominal. If you borrow $100,000 and must pay 10% interest annually, that’s $10,000 regardless of what happens to inflation.

An interest rate of 10% when inflation is 10% is therefore no more expensive for borrowers (or remunerative for lenders) than 2% interest when inflation is 2%. What matters is the gap between the nominal interest rate and inflation – known as the real interest rate – and that can even be negative. For the past decade, the real interest rate on 10-year US government debt has been hovering around zero, but recent monetary tightening combined with higher inflation has left it at around 2%. The nominal interest rate charged on dollar debt in an African renewable energy investment may rise from, say, 8% to 15% in the current environment, but that’s not necessarily a problem if nominal tariffs can rise each year to cover it – which is affordable if the nominal incomes of the household and firms who are paying those tariffs are inflating too.

Renewable energy tariffs linked to local inflation are already common, which from both the investors and customers’ perspective keeps payments steady in real terms. Some utilities, however, prefer initially high but fixed nominal tariffs because they like the prospect of inflation causing real tariffs to fall over time. Can projects be structured to make a high interest, high inflation environment less of a problem?

Before getting to that question, we must acknowledge that things get more complicated when projects are financed with dollar denominated debt but generate revenues in local currency.[1] The same principle holds: if your nominal revenue stream when converted into dollars is inflating, then covering a higher nominal interest rate on dollar debt is less of a problem. But now there are more moving parts.

If there is high inflation in the local economy, you might expect the local currency to lose value against the dollar. A project would then be in trouble if revenues were fixed in local currency, each unit of which would be worth fewer dollars. A variable, inflation-linked local currency tariff offers partial protection against that risk. We must again make a real/nominal distinction. Nominal currency depreciation is not a problem if local currency revenues are inflating fast enough to offset it. What cross-border investors are worried about is real currency depreciation, which means that the combination of exchange rate movements and local inflation still leaves the project generating fewer dollars.[2]

The most common renewables project structure pairs fixed interest rate dollar debt with tariffs tied to local inflation. To make things simpler, let’s set aside currency risk and suppose the project is able buy a hedge that fixes the local currency to dollar exchange rate.[3] Would changing that structure to incorporate a variable interest rate help? It is not unknown – there are projects structured to pay a variable rate. That is usually the rate on US treasuries plus some fixed spread but in a few markets interest rates tied to local CPI inflation are sometimes seen.

But most developers don’t like to see their projects exposed to variable interest rate risk. They don’t want the risk of the project having to make higher interest payments when revenues are not rising. Yet most lenders prefer to receive interest payments that vary with the market. The solution is that most projects are structured with an interest rate swap. That means the project pays a fixed interest rate, but what debt investors actually receive varies with market rates. Those swaps cost money, and in the current uncertain environment they will cost more, which is another source of tariff inflation.

If developers were asked to live with variable rate debt, they will look at expected future rates over the life of the loan and then price tariffs accordingly. You’d avoid the hedge fee but that saving could probably be offset by the developer charging a higher tariff to compensate the risk interest rates will turn out to higher than expected. On the other hand, while global interest rates may not have peaked, developers, financiers and governments signing deals may feel the balance of probabilities now includes more chance of falling rates over the life of a contract. When project interest rates are variable and fall, that generates upside for the developer whose earnings are higher after paying less to service debt. If you really thought that interest rates are likely to fall, you could set a lower tariff. But if interest rates really are expected to fall, that will affect the fixed rates that the hedge providers will offer too – so you’d be able to fix the interest rate at a lower level under that structure too.

If the project has an inflation-linked tariff, then what matters to the customer is its initial level. Whether structuring projects with variable interest rates will result in somewhat lower tariffs will depend on how risk averse the developers are, and what risk premia are charged by hedging providers. But it seems to me that better structuring is only going to make a marginal difference to affordability.

Customer preferences for fixed or inflation-linked tariffs may also change. If inflation will remain high, some may be more attracted to fixed nominal tariffs that fall quickly in real terms. Or inflation-linking may become more popular if off takers do not want to find themselves in a position of regretting a high fixed nominal tariff should inflation subsequently fall. Some customers may even prefer structures where a variable interest rate cost passes straight through to the tariff, because in that case the tariff should benefit from the developer not wanting a premium for bearing interest risk themselves (or alternatively for hedging it) – although that obviously exposes the customer to interest rate risk and should only be considered by those capable of managing that risk.

Having said that in principle inflation means that higher nominal rates are less of a problem, however projects are structured, investors are concerned with what they call “optics” – governments see quoted nominal tariffs rising, and do not always think in real terms. Governments may also be thinking about how price inflation is not always accompanied by income and tax revenue inflation. If inflation is high because prices of imports like fuel and food are rising, local real incomes may be squeezed. Even if tariffs are inflation-linked, the government-controlled utilities might be unwilling to pass them on (with good reason) and that puts the survival of the project at risk. Lastly, there is some devil in the detail. Debts must be serviced during the construction phase before revenues are generated, which means high nominal rates load more onto tariffs once construction is complete.

So where does this leave us? Project structures may adjust to the current high interest, high inflation environment but it’s not obvious how. And better structuring will probably only have a minor effect on the affordability of renewables in any case. A fixed nominal tariff is good for customers when inflation is high and bad from them when it’s low. Investors take the other side of that bet. A tariff that is linked to inflation protects both parties against their respective downsides and denies them their respective upsides. Relative to a fixed nominal tariff, the initial level of an inflation-linked tariff can be lower because its real value will not be eroded by inflation.

I spoke to a number of project financiers when writing this, and whilst they could see different possibilities playing out, none had strong view on how the market will react. If you do, please get in touch. Returning to the initial concern that higher nominal rates will tip the field against renewables, as illustrated by the figure below, my conclusion is things are not as bad as that looks.

Figure title: The effect of higher interested rates on the cost of electricity (source).

Figure title: The effect of higher interested rates on the cost of electricity (source).

Nominal interest rates may reach 15%, but real interest rates will not. I think the playing field will tip against renewables to the extent that real interest rates rise and that is not outweighed by higher fossil fuel costs. Plugging in nominal rates into “levelized cost of electricity” calculators tells the wrong story.

[1] Local currency lending – meaning repayments to investors are set in local currency – is a topic for another blog.

[2] Some countries also have foreign exchange liquidity problems – it is sometimes not possible to obtain dollars at quoted exchange rates, but let’s set that aside.

[3] This might simplify the argument, but it’s not realistic. Many currencies cannot be hedged in that way, and for those that can be, hedging is often only offered for the short-term.